Breast Cancer Statistics

Rates of breast cancer vary among different groups of people. Rates vary between women and men and among people of different ethnicities and ages. They vary across the U.S. and around the world.

This section provides an overview of breast cancer statistics for many populations. Click on any of the topics below to learn more.

Women

In 2024, it’s estimated among women in the U.S. there will be [179]:

- 310,720 new cases of invasive breast cancer (This includes new cases of primary breast cancer, but not breast cancer recurrences.)

- 56,500 new cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a non-invasive breast cancer

- 42,250 breast cancer deaths

Men

In 2024, it’s estimated among men in the U.S. there will be [179]:

- 2,790 new cases of invasive breast cancer (This includes new cases of primary breast cancers, but not breast cancer recurrences.)

- 530 breast cancer deaths

Rates of breast cancer incidence (new cases) and mortality (death) are much lower among men than among women [187-188].

Incidence rates in 2021 (most recent data available) and mortality rates in 2022 (most recent data available) were [187-188]:

|

Men | Women |

| Incidence rate (new cases per year) | 1.3 per 100,000 |

134.3 per 100,000 |

| Mortality rate (deaths per year) | 0.2 per 100,000 |

18.7 per 100,000 |

Learn more about breast cancer in men.

In 2024, it’s estimated among men in the U.S. there will be [179]:

- 2,790 new cases of invasive breast cancer (This includes new cases of primary breast cancers, but not breast cancer recurrences.)

- 530 breast cancer deaths

Rates of breast cancer incidence (new cases) and mortality (death) are much lower among men than among women [187-188].

Incidence rates in 2021 (most recent data available) and mortality rates in 2022 (most recent data available) were [187-188]:

|

Men | Women |

| Incidence rate (new cases per year) | 1.3 per 100,000 |

134.3 per 100,000 |

| Mortality rate (deaths per year) | 0.2 per 100,000 |

18.7 per 100,000 |

Survival

The 5-year relative survival rate for men with breast cancer is 84% [218]. This means men with breast cancer are, on average, 84% as likely to live 5 years beyond their diagnosis as men in the general population.

The 10-year relative survival rate for men with breast cancer is 74% [218].

Survival rates are averages and vary depending on each person’s diagnosis and treatment.

Learn more about survival rates.

Race and ethnicity

Male breast cancer incidence rates in the U.S. vary by race and ethnicity.

Non-Hispanic Black men have the highest breast cancer incidence rate overall [189]. Non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander men have the lowest [189].

For example, in 2021 (most recent data available) [189]:

Non-Hispanic Black |

Non-Hispanic White |

Non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander |

Hispanic |

|

Incidence rate |

2.2 per 100,000 |

1.3 per 100,000 |

0.8 per 100,000 |

0.7 per 100,000 |

Non-Hispanic Black men have higher a breast cancer mortality rate than non-Hispanic white and Hispanic men [190].

For example, in 2022 (most recent data available) [190]:

Non-Hispanic Black |

Non-Hispanic White |

Non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander |

Hispanic |

|

Mortality rate |

0.6 per 100,000 |

0.2 per 100,000 |

Not available |

0.1 per 100,000 |

Age at diagnosis

From 2017 to 2021 (most recent data available), the overall median age of breast cancer diagnosis for men in the U.S. was 69 [191]. The median is the middle value of a group of numbers, so about half of men are diagnosed before age 69 and about half are diagnosed after age 69.

The median age of breast cancer diagnosis for men is older than for women (overall, the median age at diagnosis for women is 63) [191-192].

The median age of breast cancer diagnosis for men varies by race and ethnicity.

Race and ethnicity |

Median age of breast cancer diagnosis in men |

Non-Hispanic White |

70 |

Non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander |

66 |

Non-Hispanic Black |

65 |

Hispanic |

64 |

Non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native |

Not available |

Source: 2017-2021 SEER data, 2024 [191] |

|

For example, from 2017 to 2021 (most recent data available), Black men tended to be diagnosed at a younger age than white men [191]. The median age at diagnosis for Black men was 65, compared to 70 for white men [191].

Metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis

Most often, metastatic breast cancer arises months or years after a person has completed treatment for early or locally advanced breast cancer.

Some people have metastatic breast cancer when they are first diagnosed. This is called de novo metastatic breast cancer. In the U.S., about 9% of men (and about 6% of women) have metastases when they are first diagnosed with breast cancer [193].

Learn more about metastatic breast cancer.

Breast cancer rates in men over time

From 2017 to 2021 (most recent data available), the breast cancer incidence rate in men, as well as in women, increased slightly (by less than 1% per year) [194].

The breast cancer mortality rate in men remained stable from 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available) [195]. From 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available), the mortality rate in women decreased by 1.5% per year [195].

Learn more about male breast cancer.

Learn about treatment for male breast cancer.

Breast cancer incidence rates over time

In the 1980s and 1990s, the rate of breast cancer incidence rose, largely due to increased breast cancer screening with mammography [222].

The rate of breast cancer incidence declined in the early 2000s [222]. This decline appears to be related to the drop in menopausal hormone therapy use after it was shown to increase the risk of breast cancer [62,222].

Mammography screening rates also fell somewhat in the early 2000s. However, studies show the decline in the rate of breast cancer incidence during this time was not likely due to the decline in screening rates [62-63].

From 2012 to 2021 (most recent data available), breast cancer incidence rates have increased by 1% per year [223]. Rates varied somewhat among age groups. Among women 50 and older, rates of invasive breast cancer increased by less than 1% per year and among women younger than 50, rates increased by just over 1% per year [222,224].

The increase in breast cancer incidence over time may be due, in part, to an increase in body weight and a decline in the number of births among women in the U.S. over time [64].

Trends in incidence rates of breast cancer may be different among some groups of women.

Breast cancer mortality rates over time

From 1989 to 2022 (most recent data available), the breast cancer mortality rate in U.S. women decreased by 44% due to improved breast cancer treatment and early detection [196]. Since 1989, about 517,900 breast cancer deaths in U.S. women have been avoided [222].

The breast cancer mortality rate in women decreased by about 1.5% per year from 2018 to 2022 [197]. Different breast cancer mortality rate trends may have been seen in some groups of women.

Mammography and rates of early detection over time

During the 1980s and 1990s, diagnoses of early-stage breast cancer in the U.S., including ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), increased greatly [222]. This was largely due to the increased use of screening mammography during this time [222].

Almost all cases of DCIS are diagnosed with screening mammography [222]. So, rates of DCIS increased greatly after screening mammography became widespread. Among women 50 and older, rates of DCIS increased from 7 cases per 100,000 women in 1980 to 73 cases per 100,000 women in 2000 [144]. From 2012 to 2021, rates of DCIS were stable [222].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of screening mammography declined in some groups [178].

Race/ethnicity and breast cancer incidence rates over time

The overall incidence rate of breast cancer is higher among white women than among Black women [66,198].

From 2017 to 2021 (most recent data available), the incidence rates of breast cancer in white women and Black women increased slightly (by less than 1% per year) [199].

Learn more about race/ethnicity and breast cancer risk.

Race/ethnicity and breast cancer mortality rates over time

From 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available), the mortality (death) rate from breast cancer declined for both white women (by about 1% per year) and Black women (by 1.5% per year) [200].

However, the breast cancer mortality rate from 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available) was about 37% higher for Black women than white women [201].

Figure 1.2 (below) shows the breast cancer mortality trends for Black women and white women.

Learn more about the disparities in breast cancer mortality rates between Black women and white women.

Learn more about race/ethnicity and breast cancer risk.

Figure 1.2

Age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population.

Source: 1975-2022 SEER data, 2024 [202-203]

Breast cancer rates in men over time

From 2017 to 2021 (most recent data available), the breast cancer incidence rate in men increased slightly (by less than 1% per year) [194].

The breast cancer mortality rate in men remained stable from 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available) [195].

Learn more about breast cancer in men.

Incidence rates and the number of new cases

To know whether or not breast cancer rates are changing over time, you have to compare rates, rather than the number of new cases.

For example, let’s compare the number of new cases of breast cancer in U.S. in 2009 to the number of new cases in 2016. In 2009, there were an estimated 192,370 new cases of breast cancer in U.S. women [72]. In 2016, there were an estimated 246,660 new cases [73].

Although more breast cancer cases occurred in 2016 than in 2009, this doesn’t mean the rate of breast cancer increased over this time period.

We expect the number of cases to increase over time because the population of the U.S. increases over time [74]. The more people there are, the more cancers there will be.

Our population is also living longer, so there are more people who are older [75]. Since older age is linked to an increased risk of breast cancer, we expect more breast cancers over time.

To know if breast cancer rates are changing over time, we look at incidence rates, rather than the number of new cases. The incidence rate shows the number of breast cancer cases in a set population size over a period of time. It’s usually written as the number of cases in a population of 100,000 people per year.

The breast cancer incidence rate among women in 2009 was 127 and the estimated breast cancer incidence rate in 2016 was also 127 [54]. This means there were 127 breast cancer new cases per 100,000 women in the U.S. in both 2009 and 2016.

So, although the number of breast cancer cases increased from 2009 to 2016, breast cancer rates were fairly stable.

Learn about breast cancer statistics for 2023.

Learn about breast cancer incidence rate time trends (including a figure of breast cancer incidence rates since 1975).

Survival rates and mortality (death) rates

Survival rates depend on mortality rates. You start with 100% of the people in the group.

100% – mortality rate = survival rate

Say, the mortality rate in the group of people is 5%. Survival would be 95% (100 – 5 = 95).

Similarly, the number of people in a group who survive depends on the number of people who die. Say, 500 people are in the group and 1 person dies. This means 499 people survived (500 – 1 = 499).

Mortality rates and number of breast cancer deaths

Sometimes it’s useful to have an estimate of the number of people expected to die from breast cancer in a year. This number helps show the burden of breast cancer in a group of people.

Numbers, however, can be hard to compare to each other. To compare mortality (or survival) in different populations, we need to look at mortality rates rather than the number of breast cancer deaths.

Examples of mortality rates versus number of deaths

Say, town A has a population of 100,000 and town B has a population of 1,000. Over a year, say there are 100 breast cancer deaths in town A and 100 breast cancer deaths in town B.

The number of breast cancer deaths in each town is the same. However, many more people live in town A than live in town B. So, the mortality rates are quite different.

In town A, there were 100 breast cancer deaths among 100,000 people. This means the mortality rate was less than 1% (100 deaths/100,000 people = 0.001 = 0.1% mortality rate).

In town B, the mortality rate was 10% (100 deaths/1,000 people = 0.1 = 10% mortality rate).

Although the number of deaths was the same in town A and town B, the mortality rate was much higher in town B (10%) than in town A (less than 1%).

Let’s look at another example. In 2024, it’s estimated among women there will be [179]:

- 90 breast cancer deaths in Washington, D.C.

- 710 breast cancer deaths in Alabama

- 4,570 breast cancer deaths in California

Of the 3, California has the highest number of breast cancers. However, that doesn’t mean it has the highest rate of breast cancer. These numbers don’t take into account the number of women who live in each place. Fewer women live in Alabama and Washington, D.C. than live in California.

Other factors may vary by place as well, such as the age and race/ethnicity of women. So, to compare breast cancer mortality (or survival), we need to look at mortality rates.

In 2024, the estimated mortality rates are [179]:

- 24 per 100,000 women in Washington, D.C.

- 21 per 100,000 women in Alabama

- 19 per 100,000 women in California

Even though Washington D.C. has the lowest number of breast cancer deaths, its breast cancer mortality rate is the highest of the 3 places. And, while California has the highest number of breast cancer deaths, its breast cancer mortality rate is the lowest.

Comparing mortality rates, we can see women who live in Washington D.C. have higher rates of breast cancer mortality (and thus, lower rates of breast cancer survival) than women in California.

Rates of breast cancer incidence (new cases) and mortality (death) vary across the U.S.

Incidence rates

The table below shows breast cancer incidence rates for each of the 50 states and Washington, D.C.

Hawaii, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New Hampshire have the highest breast cancer incidence rates [179]. Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico and have the lowest incidence rates [179].

For interactive maps of breast cancer incidence in the U.S., visit the National Cancer Institute (NCI) website.

Estimated Breast Cancer Incidence (New Cases) Rates among Women by State, 2016-2020 |

|||

State |

Rate of Invasive Breast Cancer |

State |

Rate of Invasive Breast Cancer |

United States |

129 |

Missouri |

131 |

Alabama |

122 |

Montana |

134 |

Alaska |

122 |

Nebraska |

131 |

Arizona |

113 |

Nevada |

111 |

Arkansas |

123 |

New Hampshire |

139 |

California |

121 |

New Jersey |

137 |

Colorado |

129 |

New Mexico |

114 |

Connecticut |

139 |

New York |

134 |

Delaware |

135 |

North Carolina |

138 |

District of Columbia |

134 |

North Dakota |

132 |

Florida |

121 |

Ohio |

130 |

Georgia |

129 |

Oklahoma |

123 |

Hawaii |

140 |

Oregon |

129 |

Idaho |

131 |

Pennsylvania |

131 |

Illinois |

133 |

Rhode Island |

140 |

Indiana |

127 |

South Carolina |

129 |

Iowa |

135 |

South Dakota |

124 |

Kansas |

132 |

Tennessee |

122 |

Kentucky |

127 |

Texas |

116 |

Louisiana |

128 |

Utah |

116 |

Maine |

128 |

Vermont |

132 |

Maryland |

133 |

Virginia |

126 |

Massachusetts |

136 |

Washington |

133 |

Michigan |

123 |

West Virginia |

120 |

Minnesota |

136 |

Wisconsin |

135 |

Mississippi |

123 |

Wyoming |

116 |

|

Source: American Cancer Society, 2024 [179] |

|||

The 2016-2020 estimated breast cancer incidence rate for Puerto Rico is 97 cases per 100,000 women [179].

Mortality rates

The table below shows breast cancer mortality rates for each of the 50 states and Washington, D.C.

Washington D.C. and Mississippi have the highest breast cancer mortality rates [179]. Hawaii and Massachusetts have the lowest breast cancer mortality rates [179].

For interactive maps of breast cancer mortality rates in the U.S., visit the NCI website.

Estimated Breast Cancer Mortality (Death) Rates among Women by State, 2017-2021 | |||

State |

Rate of Breast Cancer Mortality |

State |

Rate of Breast Cancer Mortality |

United States |

20 |

Missouri |

20 |

Alabama |

21 |

Montana |

18 |

Alaska |

17 |

Nebraska |

20 |

Arizona |

18 |

Nevada |

22 |

Arkansas |

20 |

New Hampshire |

18 |

California |

19 |

New Jersey |

20 |

Colorado |

19 |

New Mexico |

20 |

Connecticut |

17 |

New York |

18 |

Delaware |

21 |

North Carolina |

20 |

District of Columbia |

24 |

North Dakota |

17 |

Florida |

19 |

Ohio |

21 |

Georgia |

21 |

Oklahoma |

23 |

Hawaii |

16 |

Oregon |

19 |

Idaho |

20 |

Pennsylvania |

20 |

Illinois |

20 |

Rhode Island |

17 |

Indiana |

20 |

South Carolina |

21 |

Iowa |

18 |

South Dakota |

18 |

Kansas |

20 |

Tennessee |

22 |

Kentucky |

21 |

Texas |

20 |

Louisiana |

22 |

Utah |

20 |

Maine |

17 |

Vermont |

17 |

Maryland |

21 |

Virginia |

21 |

Massachusetts |

16 |

Washington |

19 |

Michigan |

20 |

West Virginia |

21 |

Minnesota |

17 |

Wisconsin |

18 |

Mississippi |

24 |

Wyoming |

19 |

Source: American Cancer Society, 2024 [179] |

|||

The 2017-2021 estimated breast cancer mortality rate for Puerto Rico is 17 deaths per 100,000 women [179].

Read our blog, Komen Answers a Global Call to Action for Breast Cancer Patients.

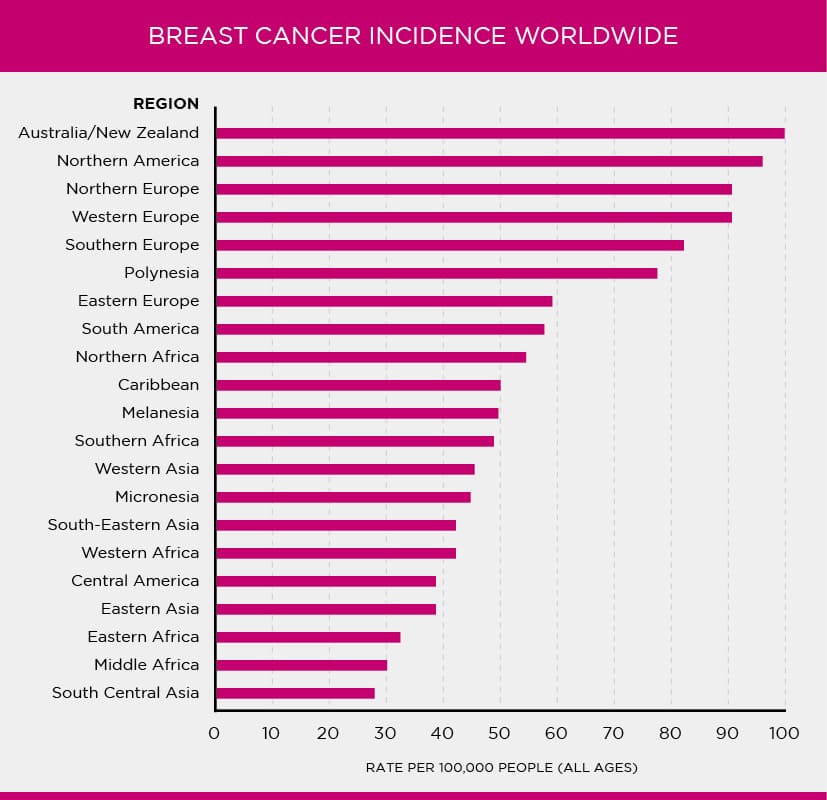

Breast cancer incidence (new cases) rates worldwide

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide.

It’s estimated more than 2 million new cases of breast cancer occurred worldwide in 2022 (most recent data available) [76].

Breast cancer incidence rates around the world vary

In general, rates of breast cancer are higher in developed countries (such as the U.S., England and Australia) than in developing countries (such as Ethiopia, Nigeria and Pakistan) [76].

Figure 1.3: Breast cancer incidence rates worldwide

Source: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) [76]

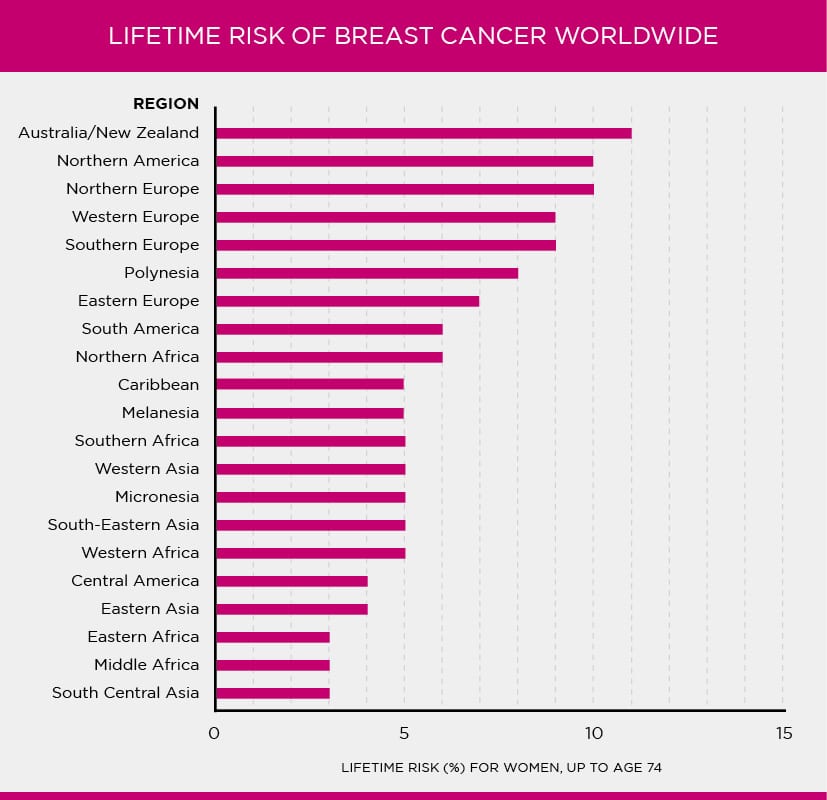

Lifetime risk of breast cancer worldwide

Women who live in developed countries tend to have a higher lifetime risk of breast cancer than women who live in developing countries [76-77].

Although we don’t know all the reasons for these differences, lifestyle and reproductive factors likely play a large role [77].

Low screening mammography rates and incomplete reporting can make rates of breast cancer in developing countries look lower than they truly are and may also explain some of these differences.

Figure 1.4: Lifetime risk of breast cancer worldwide

Source: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) [79]

Learn more about lifetime risk of breast cancer in the U.S.

Breast cancer mortality (death) rates worldwide

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality (death) among women in most countries in the world [183].

It’s estimated more than 660,000 breast cancer deaths occurred worldwide in 2022 (most recent data available) [183].

Rates of breast cancer mortality vary around the world

Breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer mortality among women in developing countries (such as Ethiopia, Nigeria and Pakistan) [77,184].

Breast cancer is the second most common cause of cancer mortality (lung cancer is first) among women in developed countries (such as the U.S., England and Australia) [77,185].

Prevalence

It’s estimated there were more than 168,000 women living with metastatic breast cancer in the U.S. in 2020 (most recent estimate available) [7].

Men can also have metastatic breast cancer.

Learn more about metastatic breast cancer.

Learn more about male breast cancer.

Metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis

Most often, metastatic breast cancer arises months or years after a person has completed treatment for early or locally advanced breast cancer.

Some people have metastatic breast cancer when they are first diagnosed. This is called de novo metastatic breast cancer. In the U.S., about 6% of women and about 9% of men have metastases when they are first diagnosed with breast cancer [204].

These rates vary by race and ethnicity. From 2012 to 2021 (most recent data available), about 9% of non-Hispanic Black women with breast cancer in the U.S. had metastases when they were first diagnosed compared to 5%-7% of women of other races and ethnicities [205].

Learn more about metastatic breast cancer.

Survival

Modern treatments continue to improve survival for people with metastatic breast cancer. However, survival varies greatly from person to person.

About one-third of women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer in the U.S. live at least 5 years after diagnosis [206]. Some women may live 10 or more years beyond diagnosis [206].

An oncologist can give some information about prognosis (expected course of disease), but they don’t know exactly how long someone will live.

Learn more about breast cancer survival rates.

Learn about treatment for metastatic breast cancer.

Breast cancer survival depends on a person’s diagnosis and treatment.

A main factor in survival is breast cancer stage. People with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or early-stage invasive breast cancer have a better chance of survival than those with later-stage breast cancers.

Measures of survival

There are different measures of survival including overall survival, breast cancer-specific survival, relative survival and population survival.

When you see a survival rate, it’s important to understand the differences between these measures. For example, breast cancer-specific survival is described below.

Breast cancer-specific survival rates

Disease-specific survival rates, such as breast cancer-specific survival, show the percentage of people who have not died from the disease over a certain period of time after diagnosis.

Five-year breast cancer-specific survival shows the percentage of people who have not died from breast cancer 5 years after diagnosis. These rates vary by breast cancer stage.

Breast Cancer Stage* |

5-Year Breast Cancer-Specific Survival |

I (1) |

98%-100% |

II (2) |

90%-99% |

III (3) |

66%-98% |

|

* Data are from people diagnosed with breast cancer who did not get neoadjuvant therapy Adapted from Weiss et al. [81] |

|

Learn more about survival statistics.

In the U.S., most people diagnosed with breast cancer will live for many years. Today, there are more than 4 million breast cancer survivors in the U.S. (more than any other group of cancer survivors) [142].

At Susan G. Komen®, we view anyone who has been diagnosed with breast cancer as a survivor, from the time of diagnosis through the end of life. The National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Survivorship and the American Cancer Society use similar definitions [142-143]. We recognize that not everyone who’s been diagnosed with breast cancer will identify with this term or see themselves as a survivor.

Learn more about survivorship.

Time trends

After mammography was shown to be an effective breast cancer screening tool in the late 1980s, the use of screening mammography in the U.S. quickly increased.

In 1987, 29% of women 40 years and older reported having a screening mammogram within the past 2 years [82]. By 2000, mammography use increased to 70% [82].

Since 2000, there has been a slight decline in screening mammography use for reasons that remain unknown [82,178]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of screening mammography declined in some groups [178].

In 2021 (most recent data available), 64% of women in the U.S. ages 45 and older reported having a screening mammogram within the past year [178]. And, about 76% of women ages 50-74 had a screening mammogram in the past 2 years [178]. Mammography rates, however, vary by group.

Age

In 2021 (most recent data available):

Age |

Percentage of women ages 45-54 who had a screening mammogram within the past year |

Percentage of women ages 55 and older who had a screening mammogram within the past 2 years |

45-54 |

50% |

NA |

55-64 |

NA |

76% |

65-74 |

NA |

77% |

75 and older |

56% |

NA |

NA = Not applicable Adapted from American Cancer Society materials [178]. |

||

Learn more about how rates of screening mammography vary among different groups of women.

Race/ethnicity

In 2021 (most recent data available):

Race/ethnicity |

Percentage of women ages 50-74 who had a screening mammogram within the past 2 years |

Black |

82% |

White |

76% |

Hispanic |

74% |

Asian |

67% |

American Indian and Alaska Native |

59% |

Adapted from American Cancer Society materials [178]. |

|

Learn more about how rates of screening mammography vary among different groups of women.

Health insurance

Women who don’t have health insurance are much less likely to get screening mammograms than women with health insurance.

In 2021 (most recent data available):

Has health insurance? |

Percentage of women ages 50-74 who had a screening mammogram within the past 2 years* |

Yes, private health insurance |

80% |

Yes, Medicaid |

71% |

No |

42% |

* For women ages 65 and older who were on Medicare, 75% had a mammogram within the past 2 years. Adapted from American Cancer Society materials [178]. |

|

Since September 2010, the Affordable Care Act has required all new health insurance plans to cover screening mammograms with no co-payment [83]. Health plans must cover mammography at least every 2 years for women 50 and older, and as recommended by a health care provider for women 40-49 [83].

Learn about Medicare, Medicaid and insurance company coverage of mammograms and find resources for low-cost or free mammograms.

Learn more about how rates of screening mammography vary among different groups of women.

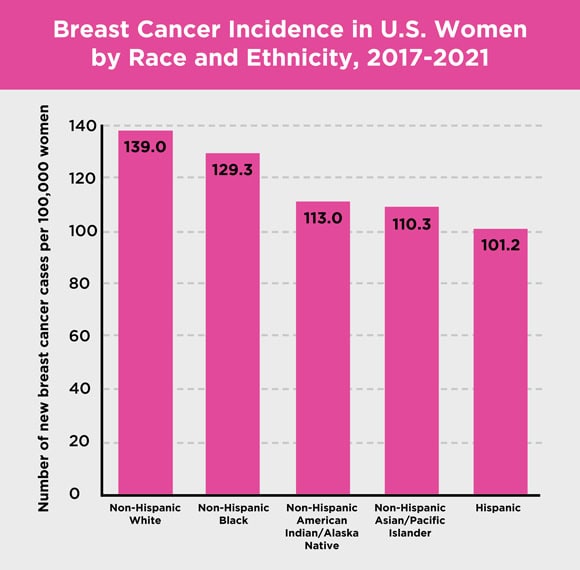

Among women in the U.S., rates of breast cancer incidence (new cases) and mortality (death) vary by race and ethnicity.

Figure 1.7

Source: 2017-2021 SEER data, 2024 [198]

Non-Hispanic white women and non-Hispanic Black women have the highest rates of breast cancer incidence overall [198]. Hispanic women have the lowest [198].

Figure 1.8

Source: 2018-2022 SEER data, 2024 [201]

Non-Hispanic Black women have the highest breast cancer mortality rate overall [201]. Non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander women have the lowest [201].

Click on the topics below to learn more about rates of breast cancer incidence and mortality among women of different races and ethnicities.

Immigrants in the U.S. usually have breast cancer incidence (new cases) rates similar to those in their home countries.

However, the daughters and granddaughters of immigrants tend to adopt American lifestyle behaviors. These may include things that increase breast cancer risk, such as being overweight or having children later in life.

So, over time, breast cancer incidence rates in the daughters and granddaughters of immigrants tend to become closer to overall incidence rates in the U.S.

Ashkenazi Jewish heritage and BRCA1 and BRCA2 inherited gene mutations

Everyone has BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) genes, but people with an inherited mutation in either of these genes have an increased risk of breast cancer and other cancers [91-95,174-175].

BRCA1/2 inherited gene mutations are more common in Jewish people of Eastern European descent (Ashkenazi Jews) than in other people [174-175].

BRCA1/2 inherited mutations are rare in the general U.S. population (about 1 in 400 people) [174]. However, about 1 in 40 Ashkenazi Jewish people in the U.S. carry one of these gene mutations [174].

Learn more about Ashkenazi Jewish heritage and breast cancer risk.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 inherited gene mutations and cancer risk

Women who have a BRCA1/2 inherited gene mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer [91-95,174-175].

Men who have a BRCA2 inherited gene mutation, and to a lesser degree men who have a BRCA1 inherited gene mutation, have an increased risk of breast cancer [91,93,98-100,174-175].

Learn more about BRCA1/2 inherited gene mutations and the risk of breast and other cancers in women.

Learn more about BRCA1 /2 inherited gene mutations and the risk of breast and other cancers in men.

Learn about genetic testing for BRCA1/2 inherited gene mutations.

Rates of breast cancer incidence (new cases) and mortality (death) are lower for non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander women than for non-Hispanic white women and non-Hispanic Black women [198,201].

For example, incidence rates from 2017 to 2021 and mortality rates from 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available) were [198,201]:

Non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander women |

Non-Hispanic White women |

Non-Hispanic Black women |

|

Incidence rate |

110.3 per 100,000 |

139.0 per 100,000 |

129.3 per 100,000 |

Mortality rate |

11.9 per 100,000 |

19.4 per 100,000 |

26.8 per 100,000 |

Prevalence

As of January 2021 (most recent data available), there were about 168,000 non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander women in the U.S. who were breast cancer survivors or were living with breast cancer [207].

Incidence (new cases) rates

The incidence rate of breast cancer in non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander women increased slightly from 2017 to 2021 by about 3% a year [199].

Immigrants in the U.S. (including those from Asia) usually have breast cancer incidence rates similar to those in their home countries.

However, the daughters and granddaughters of immigrants tend to adopt American lifestyle behaviors. These may include things that increase breast cancer risk, such as being overweight or having children later in life. Over time, breast cancer incidence rates for the daughters and granddaughters of immigrants may become closer to incidence rates in the U.S.

Breast cancer incidence rates vary among women from different Asian American ethnic groups [101]. For example, the incidence rate is higher in Samoan American and Hawaiian women than in Chinese American and Vietnamese American women [101].

Mortality (death) rates

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in Asian American women (lung cancer is the major cause of cancer death) [180].

The breast cancer mortality rate for non-Hispanic Asian American women remained stable from 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available) [208].

Breast cancer mortality rates vary among women from different Asian American ethnic groups [219]. For example, breast cancer mortality rates for Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander women are higher than breast cancer mortality rates for Asian American women [219].

Breast cancer survival

From 2014 to 2020 (most recent data available), the 5-year relative breast cancer survival rate for non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander women in the U.S. (92%) was about the same as the 5-year relative survival rate for non-Hispanic white women (93%) [209].

This means non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander women were 92% as likely as women in the general population to live 5 years beyond their breast cancer diagnosis. Non-Hispanic white women were 93% as likely as women in the general population to live 5 years beyond diagnosis.

Breast cancer survival rates vary among women from different Asian American ethnic groups [219]. For example, the 5-year relative survival rate for Japanese American women is higher than for Native Hawaiian women [219].

Similarly, rates of early-stage diagnosis vary among women from different Asian American ethnic groups [219]. For example, from 2016-2020 (most recent data available), 73% of Japanese American women were diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer that hadn’t spread to the lymph nodes compared to 47% of Samoan American women [219].

Breast cancer screening

In 2021 (most recent data available), Asian American women had lower rates of screening mammography compared to Black women, white women and Hispanic women [178].

Rates of screening mammography vary among women from different Asian American ethnic groups [219].

Learn more about breast cancer screening among Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander women.

Prevalence

As of January 2021 (most recent data available), there were about 361,000 Black women in the U.S. who were breast cancer survivors or were living with breast cancer [207].

Incidence (new cases)

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among Black women [180].

In 2022, about 36,260 new cases of breast cancer were expected to occur among Black women [66].

Overall, the breast cancer incidence rate among non-Hispanic Black women is lower than among non-Hispanic white women [198].

The incidence rate of breast cancer in Black and non-Hispanic Black women increased slightly from 2017 to 2021 (by less than 1% a year) [199].

Age at diagnosis

Non-Hispanic Black women who develop breast cancer tend to be diagnosed at a younger age than non-Hispanic white women [211].

From 2017 to 2021, the median age at diagnosis for non-Hispanic Black women was 61, compared to 65 for non-Hispanic white women [211].

The median is the middle value of a group of numbers, so about half of non-Hispanic Black women were diagnosed before age 61 and about half were diagnosed after age 61. Among non-Hispanic white women, about half were diagnosed before age 65 and about half were diagnosed after age 65.

Mortality (death)

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in Black women (lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death) [180].

In 2022, about 6,800 breast cancer deaths were expected to occur among Black women [66].

From 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available), the breast cancer mortality rate declined for Black and non-Hispanic Black women by about 1% per year [208].

However, the breast cancer mortality rate from 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available) was about 37% higher for Black women than white women [201].

Survival

Although breast cancer survival in non-Hispanic Black women has increased over time, survival rates remain lower than among white and non-Hispanic white women [173].

For those diagnosed from 2014 to 2020 (most recent data available), the 5-year relative survival rate for breast cancer among non-Hispanic Black women was 84% compared to 93% among non-Hispanic white women [209].

This means non-Hispanic Black women were 84% as likely as women in the general population to live 5 years beyond their breast cancer diagnosis. Non-Hispanic white women were 93% as likely as women in the general population to live 5 years beyond diagnosis.

There are many possible reasons for this difference in survival including [66,90,103-105,222]:

- Differences in tumor biology and tumor genetics

- Later stage of breast cancer at diagnosis

- Barriers to high-quality health care access (including a lack of health insurance)

- Differences in the percentage of women who have certain risk factors (including being overweight)

- Not completing treatment

For example, breast cancer stage at diagnosis is important to survival. Stage IV is the most advanced stage (also called stage 4 or metastatic breast cancer). From 2012 to 2021 (most recent data available), about 9% of non-Hispanic Black women with breast cancer in the U.S. had stage IV when they were first diagnosed compared to 5%-7% of women of other races and ethnicities [205].

Learn about healthy lifestyle behaviors and breast cancer survival.

Learn about Komen’s commitment to health equity.

Breast cancer screening

In 2021 (most recent data available), Black women had higher rates of screening mammography than other women [178].

Learn more about breast cancer screening among Black women.

Rates of breast cancer incidence (new cases) and mortality (death) for Hispanic women are lower than for non-Hispanic white women and non-Hispanic Black women [198,201].

For example, incidence rates from 2017 to 2021 and mortality rates from 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available) were [198,201]:

Hispanic women |

Non-Hispanic White women |

Non-Hispanic Black women |

|

Incidence rate |

101.2 per 100,000 |

139.0 per 100,000 |

129.3 per 100,000 |

Mortality rate |

13.7 per 100,000 |

19.4 per 100,000 |

26.8 per 100,000 |

Prevalence

As of January 2021 (most recent data available), there were about 294,000 Hispanic women in the U.S. who were breast cancer survivors or were living with breast cancer [207].

Incidence (new cases)

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in Hispanic/Latina women [180].

In 2024 (most recent data available), an estimated 31,500 new cases of breast cancer will be diagnosed among Hispanic women in the U.S. [106].

The incidence rate of breast cancer in Hispanic/Latina women increased slightly from 2017 to 2021 (by about 1% a year) [199].

From 2017 to 2021 (most recent data available), the breast cancer incidence rate was about 26% lower in Hispanic women than in non-Hispanic white women [198].

From 2012 to 2021 (most recent data available), about 6% of Hispanic women and about 6% of non-Hispanic white women had metastatic breast cancer when they were first diagnosed with breast cancer [205]. Metastatic breast cancer is also called stage IV (4) or advanced breast cancer.

Lifetime risk of getting breast cancer

The lifetime risk of breast cancer for Hispanic women is lower than the lifetime risk of breast cancer for non-Hispanic white women [220]. One in 9 Hispanic women will get breast cancer in her lifetime compared to 1 in 7 non-Hispanic white women [220].

Mortality (death)

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in Hispanic women [106,180].

In 2024 (most recent data available), an estimated 3,700 breast cancer deaths will occur among Hispanic/Latina women in the U.S. [106].

The breast cancer mortality rate in Hispanic women decreased slightly from 2018 to 2022 (by less than 1% a year) [208].

From 2018 to 2021 (most recent data available), the breast cancer mortality rate was about 29% lower in Hispanic women than in non-Hispanic white women [201].

Lifetime risk of dying from breast cancer

The lifetime risk of dying from breast cancer for Hispanic women is lower than the lifetime risk of dying from breast cancer for non-Hispanic white women [221]. About 1 in 55 Hispanic women will die from breast cancer in her lifetime compared to 1 in 43 non-Hispanic white women [221].

Survival

For those diagnosed from 2014 to 2020 (most recent data available), the 5-year relative survival rate for breast cancer among Hispanic women was 88% compared to 93% among non-Hispanic white women [209]. One reason for this difference may be a smaller percentage of Hispanic women being diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer compared to white women [106,205].

Breast cancer screening

In 2021 (most recent data available), Hispanic women had similar rates of screening mammography as white women, but lower rates of screening mammography compared to Black women [178].

Screening mammography rates among Hispanic women vary by group. For example, women of Central/South American origin have higher screening mammography rates than Mexican American women [106].

Hispanic women tend to be diagnosed with later stage breast cancers than non-Hispanic white women [90,106].

Learn more about breast cancer screening among Hispanic/Latina women.

Breast cancer incidence (new cases) and mortality (death) rates are lower in Non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native women than in non-Hispanic white women and non-Hispanic Black women [198,201].

For example, incidence rates from 2017 to 2021 and mortality rates from 2018 to 2022 (most recent data available) were [198,201]:

Non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native women |

Non-Hispanic White women |

Non-Hispanic Black women |

|

Incidence rate |

113.0 per 100,000 |

139.0 per 100,000 |

129.3 per 100,000 |

Mortality rate |

17.8 per 100,000 |

19.4 per 100,000 |

26.8 per 100,000 |

Prevalence

As of January 2021 (most recent data available), there were about 12,000 non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native women in the U.S. who were breast cancer survivors or were living with breast cancer [207].

Incidence (new cases)

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in American Indian and Alaska Native women [180]. However, breast cancer incidence rates vary depending on where women live.

American Indian and Alaska Native women who live in the Southern Plains, the Northern Plains and Alaska have the highest breast cancer incidence rates, even higher than incidence rates among white women in these areas [53,86-87]. Women who live in the Southwest and the East have lower rates [53,86-87].

Breast cancer incidence rates in non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native women increased slightly from 2017 to 2021 (most recent data available), by about 1.5% a year [199].

Mortality (death)

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among American Indian and Alaska Native women (lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death) [180].

The breast cancer mortality rate in non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native women remained stable from 2018 to 2022 [208].

Survival

For those diagnosed from 2014 to 2020 (most recent data available), the 5-year relative survival rate for breast cancer among non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native women was 88% compared to 93% for non-Hispanic white women [209].

This means non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native women were 88% as likely as women in the general population to live 5 years beyond their breast cancer diagnosis. Non-Hispanic white women were 93% as likely as women in the general population to live 5 years beyond diagnosis.

However, American Indian and Alaska Native women are less likely than white women and non-Hispanic white women to be diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer that hasn’t spread to the lymph nodes [90,205].

Breast cancer screening

In 2021 (most recent data available, though data were limited), American Indian and Alaska Native women had lower rates of screening mammography than other women [178].

Screening mammography rates among American Indian and Alaska Native women vary depending on where women live [53]. Women who live in the Southern Plains and Alaska have higher rates of screening mammography than women who live in the Pacific Coast region [53].

Learn more about breast cancer screening among Native American and Alaska Native women.

Listen to our Real Pink podcast, Breast Health in the LGBTQ+ Community.

In 2021, about 7% of all adults in the U.S. reported being lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, or other diverse sexual orientation or gender identity [179]. Among younger adults, about 20% report diverse sexual orientation or gender identity [179].

Gay, lesbian and bisexual women

Breast cancer rates

Although lesbians and bisexual women tend to have an increased risk of breast cancer, it’s not due to their sexual orientation.

Rather, studies show the increased risk of breast cancer is linked to risk factors that tend to be more common in lesbians such as never having children or having them later in life, obesity and alcohol use [107-109,179].

Learn more about factors linked to an increased risk of breast cancer.

Breast cancer screening

Screening mammography rates among lesbians and bisexual women are similar to screening mammography rates among heterosexual women [178-179].

In 2021 (most recent data available) [179]:

- 78% of gay and lesbian women ages 50-74 had a mammogram in the past 2 years

- 76% of straight women ages 50-74 had a mammogram in the past 2 years

Data on screening mammography in transgender people and nonbinary people are limited.

Some lesbian and bisexual women may not get regular mammograms. Studies show this may be due to [111-112,179]:

- Lack of health insurance

- Perceived low risk of breast cancer

- Past discrimination or insensitivity from health care providers

- Low level of trust of health care providers

- Having trouble finding a health care provider

Resources for finding a health care provider

It’s important to find a health care provider who is sensitive to your needs. Getting a referral from a trusted friend may help. The National LGBT Cancer Network has a directory of LGBT-welcoming cancer screening centers that may also be helpful.

Regular visits to a health care provider offer the chance to discuss your risk of breast cancer and get breast cancer screening and other needed health care.

Learn more about finding a health care provider.

Find resources for breast cancer support and financial assistance.

Transgender people

Transmasculine people (transgender men) had female sex assigned at birth but have male gender identity. Transfeminine people (transgender women) had male sex assigned at birth but have female gender identity.

Data on breast cancer among transmasculine and transfeminine people are limited.

A few small studies have compared breast cancer rates among transgender people who had hormone treatments, with or without surgery as part of their transition, to breast cancer rates in the general population [113,212]. These early findings suggest [113,212]:

- Transmasculine people have a much lower risk of breast cancer than women in the general population, but a higher risk than men in the general population.

- Transfeminine people have a much lower risk of breast cancer than women in the general population, but a higher risk than men in the general population.

There’s still much to learn about the risk of breast cancer in transgender people. If you’re transgender, talk with your health care provider about your risk of breast cancer.

Learn about breast cancer screening recommendations for transgender people.

Resources for finding a health care provider

It’s important to find a health care provider who is sensitive to your needs. Getting a referral from a trusted friend may help. The National LGBT Cancer Network has a directory of LGBT-welcoming cancer screening centers that may also be helpful.

Regular visits to a health care provider offer the chance to discuss your risk of breast cancer and get breast cancer screening and other needed health care.

Learn more about finding a health care provider.

Find resources for breast cancer support and financial assistance.

Everyone is at risk of breast cancer.

The most common risk factors of breast cancer are:

- Being born female

- Getting older

The risk of getting breast cancer increases with age. Most breast cancers and breast cancer deaths occur in women 50 and older [222].

The overall median age at diagnosis for women in the U.S. is 63 [192]. The median is the middle value of a group of numbers, so about half of women are diagnosed before age 63 and about half are diagnosed after age 63. The median age at diagnosis for U.S. women varies by race and ethnicity.

Learn more about age and breast cancer risk.

Women younger than 40

About 4% of breast cancers occur in women younger than 40 [222].

However, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death (death from any type of cancer) among women ages 20-39 [180].

Genetic factors can put some younger women at a higher risk of breast cancer. Women diagnosed younger than 40 may have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 inherited gene mutation. These inherited gene mutations increase the risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer.

Learn more about BRCA1, BRCA2 and other inherited gene mutations and breast cancer risk.

Learn about breast cancer screening for women who have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 inherited gene mutation.

Learn about unique issues for younger women diagnosed with breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in pregnant and postpartum women [213]. It occurs most often between ages 32 and 38 [213].

About 1 case of breast cancer in 3,000 pregnancies is diagnosed each year [213].

When women are pregnant or breastfeeding, their breasts naturally become more tender and enlarged. This may make it harder to find a lump or notice other changes in the breasts.

Learn more about breast cancer during pregnancy.

It takes time to carefully collect, sort and analyze data. So, often, the “most recent data available” are several years old.

The larger the amount of data involved, the longer the process can take. For example, when researchers collect data from many different states or countries, rather than from one hospital, it takes much longer.

Sometimes, researchers need to collect data over many years.

Say researchers want to learn about survival 5 years after a breast cancer diagnosis. They must collect data on people diagnosed this year and then wait 5 years to collect the data on 5-year survival. Only then can they begin to sort and analyze the data.

So, when you see the most recent data are from 2020 or 2021, it doesn’t mean the data are “old.” It simply means it took time to carefully collect the data, do the analyses and prepare the findings.

Updated 10/04/24